News

Sharpening focus on eye clinical trials

Clinical trials collect the evidence needed to prove new drugs and treatments work, and improve outcomes for patients.

Clinical trials play a critical role in developing new treatments to prevent blindness, as innovative new technologies offer hope for people with previously untreatable eye diseases.

But as cutting-edge technologies like gene therapy and artificial intelligence transform eye clinical trials – the fundamental principle of research has remained unchanged for more than 250 years.

In 1747 Scottish naval doctor James Lind selected 12 men suffering from scurvy and divided them into six groups.

He supplied each group a different suspected treatment for the disease, ranging from cider to sea water, and carefully observed their condition.

The two men who were given oranges and lemons, both rich sources of vitamin C, improved so quickly they were able to nurse the others in the group.

Lind’s basic design of a fair, comparative and controlled ‘like-for-like’ study is still the fundamental basis of all modern clinical trials, including those performed today at the Centre for Eye Research Australia.

“Clinical trials are critical to collecting the evidence that is needed to prove new drugs and treatments work, and improve outcomes for patients,” says Head of CERA’s Clinical Trials Research Associate Professor Lyndell Lim.

Clinical trials at CERA

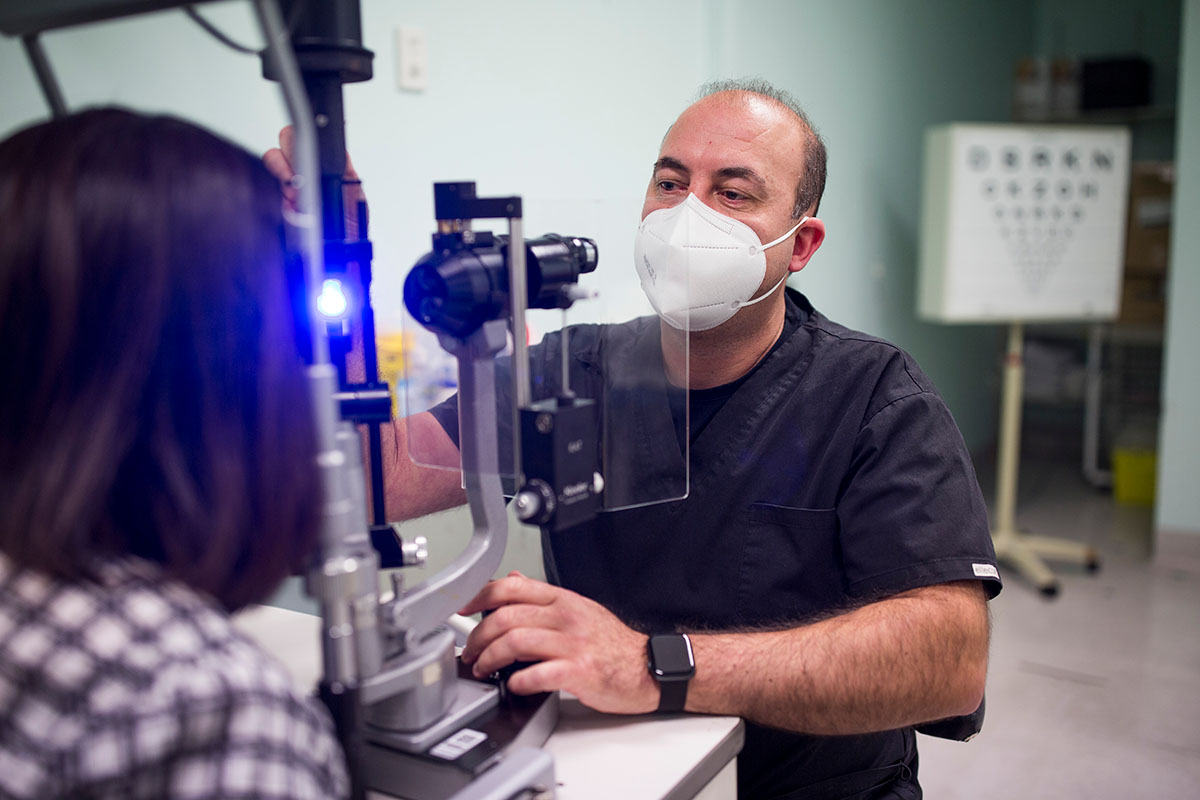

Associate Professor Lim leads CERA’s Clinical Trial Research Centre which conducts trials for clinician-researchers, universities, pharmaceutical companies and biotech enterprises from around the world.

Her team administers more than 30 trials annually for a broad range of eye diseases including age-related macular degeneration, diabetic eye disease, glaucoma and uveitis from its base at the Royal Victorian Eye and Ear Hospital in East Melbourne and a network of community clinics.

Their work is complemented by an extensive clinical research program involving CERA’s Macular Research Unit led by Professor Robyn Guymer AM and a fast-emerging retinal gene therapy research program led by Dr Tom Edwards.

Last year CERA’s retinal gene therapy researchers joined forces to with colleagues from the Eye and Eye Hospital to deliver Australia’s first investigational gene therapy for dry age-related macular degeneration.

They were also a part of another global study investigating the use of an anti-oxidant as a potential treatment to prevent vision loss from retinitis pigmentosa in people with Usher Syndrome.

Identifying participants

Identifying suitable people to take part in research is an important factor in running a successful clinical trial.

CERA’s close partnerships with the Eye and Ear Hospital, private ophthalmologists and a growing network of optometrists provides a rich source of participants.

Two large natural history studies – of people with age-related macular degeneration and inherited retinal diseases – have enabled CERA to link people with these conditions to suitable trials when new potential treatments emerge.

In the case of people with conditions like ‘dry’ age-related macular degeneration and inherited retinal diseases, for which there are currently no approved treatments, taking part in a trial offers access to potentially sight-saving treatments.

Successful clinical research also relies on understanding what matters to patients and their families – as well as ensuring that they are well informed about the role of research.

CERA and the University of Melbourne conducted Australia’s first survey of patients with inherited retinal disease which about their views on potential gene therapies. These findings will provide a valuable resource for future trials.

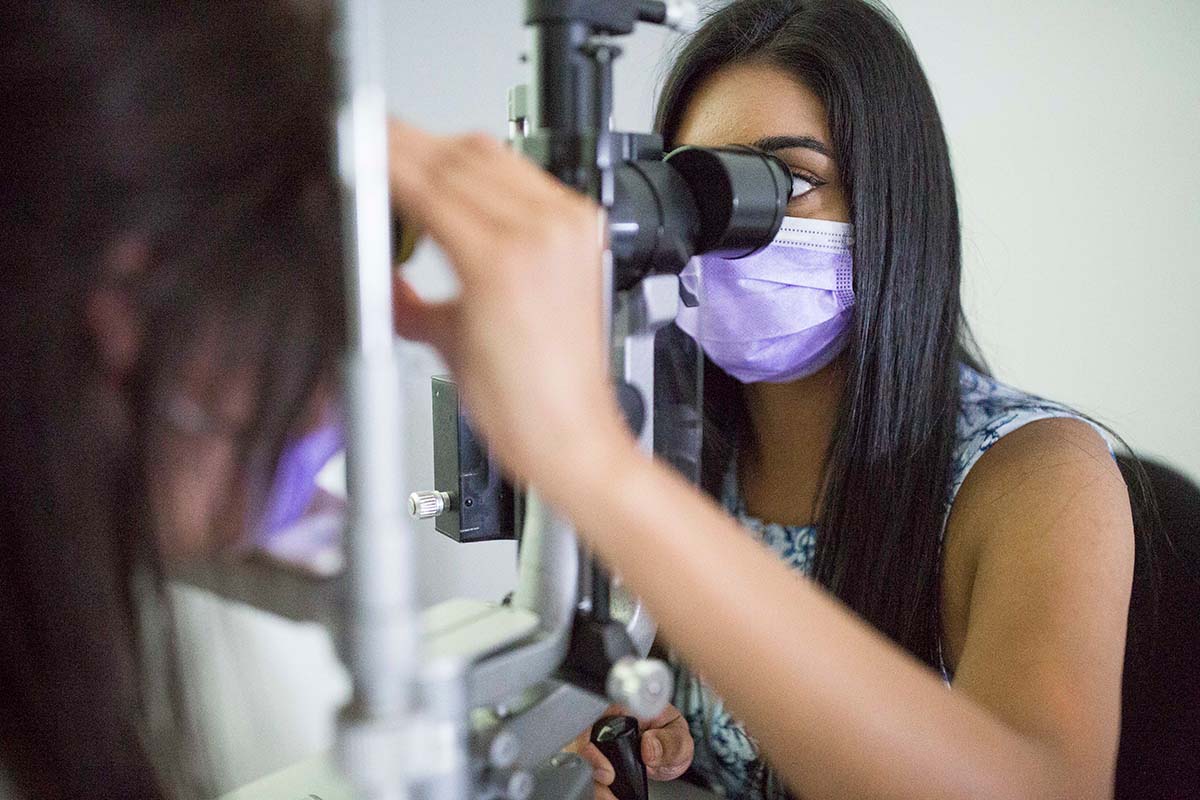

Screening process

When a person is being considered to take part in a clinical trial they must first undergo a thorough screening to assess their suitability, as well has have a thorough discussion with study doctors and coordinators to understand how the trial will operate.

Suitable patients are then assigned to a treatment group.

Clinical trials typically compare a new treatment to standard current treatments, although if there is no current treatment it is compared to a placebo, or ‘pretend’, treatment.

To make sure the results are fair, patients are randomly assigned to treatment groups, and both study participants and doctors do not necessarily know who is in each group.

Changing lives

CERA Managing Director Professor Keith Martin, who has been an ophthalmologist and vision researcher for more than 25 years says there has never been a more exciting time in eye research – for patients, clinicians and scientists.

“Less than a decade ago, someone with an inherited retinal disease (IRD), or a condition like dry age macular degeneration or even glaucoma that is not responding to the conventional treatments, would be told there was nothing that could be done for their condition.

“But now gene therapies are offering real prospects of saving – and even restoring sight.’’

Just like Lind’s original research into scurvy, the ongoing to work of clinical trials is crucial to bringing life-changing treatments to people.

Take part in research

If you are interested in taking part in a clinical trial at CERA visit our Take Part in Research page for more information and to register your interest.