News

Billy’s focus on the future

Billy Morton was diagnosed with a rare genetic eye disease in his teens. Today he’s taking the challenge of living with vision loss in his stride.

When Billy Morton is not studying or working, you’ll find him blazing a trail alongside the Yarra River. The 22-year-old runs around 80 kilometres a week, prioritising his regular exercise in a schedule that also includes university commerce studies, part-time work and – outside of lockdown – hanging out with friends and playing social netball.

“Running is more than physical. It definitely helps take my mind off of things, and gives my mind a good break,’’ he says. “It gives me a sense of independence and freedom.’’

A diagnosis of choroideremia

In his early teens Billy was diagnosed with choroideremia, a rare genetic eye disease that causes degeneration of the layers of the retina, the light-sensitive cells at the back of the eye which are essential for vision.

Choroideremia, which usually affects young men, often starts with night blindness in childhood or the teen years, followed by a progressive loss of peripheral vision throughout adulthood which eventually results in tunnel vision – and sometimes, as people get older, full loss of central vision.

There is currently no treatment or cure for choroideremia.

But so far, the disease has not stopped Billy from doing the things he wants to. He doesn’t have a driver’s licence but other than that his life is similar to many others his age.

“Sometimes I have to use my mobile phone to see in dark places like clubs or cinemas – but I can use the light on my mobile phone and I’m often with friends,’’ he says.

Billy’s best mate since high school, Callum Blackburn, says he often forgets his friend has a vision problem.

“It’s not something we talk about,’’ he says. “It’s not that Billy is trying to hide it – but he just gets out there and makes the most out of every situation. It’s only sometimes when it’s dark and there might be an obstacle in the way that he’ll reach out for someone’s shoulder.

Navigating uncertainty

Choroideremia carries an uncertain prognosis – and it’s hard to predict how quickly someone’s vision will decline.

People with the disease experience progressive vision loss throughout life – but it is different for everyone and for some people the rate of vision loss is faster and more severe.

Billy’s parents Andrew and Beth recall keeping a night light on in the bathroom when the children were small and noticed that Billy found it very difficult to see at night. “We would be at basketball and notice that he would miss rebounds or things that happened on the court, or knock things over,’’ says Beth.

Choroideremia runs in families, passed on via a genetic mutation in X-chromosome.

Women who carry the mutation often have very mild, or no symptoms at all.

Billy’s cousin Sam Harding, a competitor in the athletics in this year’s Tokyo Paralympics, had been diagnosed with the disease as a child. Armed with this knowledge, the Mortons headed to eye specialists and for genetic testing. “Even though we knew Sam had choroideremia, initially Billy’s diagnosis was a shock,’’ says Beth.

“We certainly knew there was a problem – but didn’t realise the great impact that it had on Billy’s peripheral vision and anticipate it will get worse.

“But from that point we carried on – and when he was first diagnosed Billy had good vision and it didn’t affect his schooling.’’

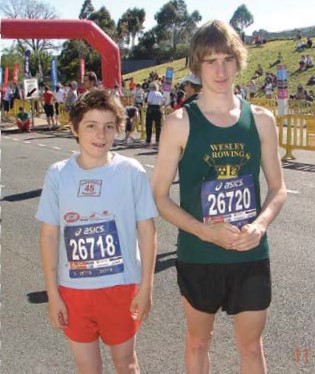

At his secondary school, Xavier College, Billy focused on the positives. When his sight made playing basketball difficult, he started rowing.

“Billy is always talking about what he is doing, not what he can’t do,’’ says his dad, Andrew Morton. “He is very focused on what he wants to do, he is interested in politics and economics and cares about social justice.’’

After Year 12 – inspired by a talk at Xavier – Billy and Callum took a gap year to volunteer in a school in Sri Lanka.

Motivated by that time, he now aspires for a career as an economist and would like to work in government.

“I am fascinated by how the decisions that are made at an economic level can make a difference for people,’’ says Billy. “It is also a career where I don’t have to rely on my vision and that I can still do if I lose my sight in my 40s.’’

Changing the future

Billy is currently part of a natural history study between CERA and the University of Melbourne to learn more about people with choroideremia and other inherited retinal diseases (IRDs).

Until recent years, because of the lack of treatments, there has been little research into how the disease progresses or a likely prognosis for patients.

But now with rapid advances in gene and cell therapy research, propelled by the emergence of cutting-edge technologies like CRISPR gene editing, there is hope for the future.

Natural history study leader Associate Professor Lauren Ayton says her team aims to create a database of people with information about their vision, their genetic profile and if they are want to take part in clinical trials.

“This means that when new treatments and trials come up, we will have people ready to take part,” she says.

Hope in sight

Andrew Morton says that when Billy was first diagnosed there was no prospect of a treatment.

“The idea of a treatment just wasn’t on the radar. In a decade the research has really moved forward.’’

Beth says watching her nephew Sam’s vision loss progress gave the family some idea of what Billy’s prognosis could be – but research was offering hope to families.

“It gives you hope that there may be some deterioration that will be halted, that would be really amazing.’’

Like many young people, Billy is concerned about the future and says he’s ‘not super optimistic’ about the state of the world.

“Despite this there are so many things going on that are incredibly exciting that make me hopeful and optimistic. When you look at things like gene therapy and the way the science is moving– things like data and AI – there are so many great examples about how these technologies are being used to make a difference.

“For now, I just make the most of every day and appreciate what I have without worrying about the things I can’t control.

“Hopefully there will be research that will benefit me, but, if not, it is exciting to know that it could make a difference for other people.’’

More information

For details on taking part in CERA’s natural history study contact IRDgroups@unimelb.edu.au