Professor Keith Martin welcomed to Australian Academy of Health and Medical Sciences

News

Professor Keith Martin welcomed to Australian Academy of Health and Medical Sciences

As he is elected as a Fellow of the Australian Academy of Health and Medical Sciences, CERA Managing Director Professor Keith Martin says the future of eye research is not only about preserving vision but also restoring sight.

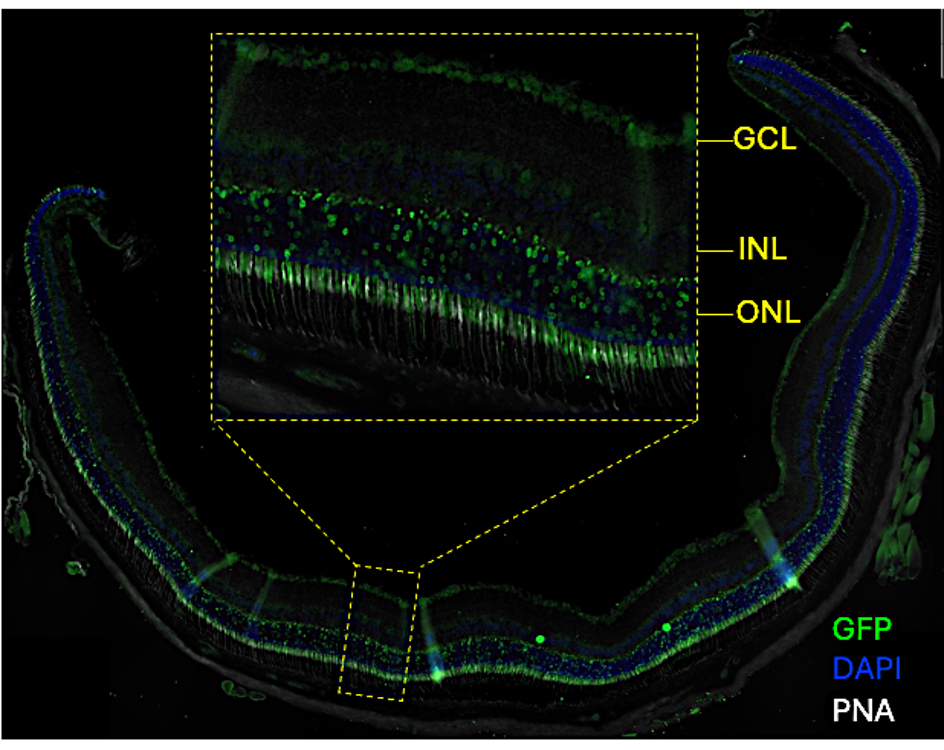

CERA Managing Director Professor Keith Martin has dedicated his career to finding better ways to treat glaucoma, including a pioneering gene therapy that is now progressing towards human trials.

Before his current roles leading CERA and as the Ringland Anderson Professor and Head of Ophthalmology at the University of Melbourne, Professor Martin was head of Ophthalmology and Deputy Director of the Centre for Brain Repair at the University of Cambridge.

After being elected as a 2025 Fellow of the Australian Academy of Health and Medical Sciences (AAHMS) for his achievements as a researcher and advocate for medical research, Professor Martin shares how the opportunity to transform lives drives his passion for eye research.

What led you to ophthalmology as a career and, by extension, research in ophthalmology?

I was drawn to ophthalmology because it combines the precision of microsurgery with the profound privilege of preserving and restoring sight.

From the outset, I was fascinated by the complexity of the eye as an extension of the brain, and by how advances in neuroscience could be translated to protect vision.

My research path grew naturally from that curiosity – trying to understand why retinal ganglion cells die in glaucoma, and how we might one day replace or regenerate them.

It’s a field where scientific discovery and future clinical impact are tightly intertwined, and that balance has kept me captivated ever since.

What about research gets you most excited to come to work in the morning?

What excites me most is the possibility that today’s ideas could become tomorrow’s treatments.

It is exciting to see hypotheses evolve into therapies that might change the lives of patients who currently have no options.

I’m also inspired daily by the people I work with – our students, clinicians, and scientists who share a belief that the impossible can become achievable with the right combination of persistence, creativity, and collaboration.

The sense that we are contributing, even in small ways, to something much larger than ourselves is what keeps me motivated.

Can you pinpoint the most rewarding moment of your career so far?

It is hard to pinpoint one moment, but operating on children with congenital glaucoma and knowing I have given them a chance to retain their sight for life rather than face inevitable blindness has to come close.

I want to be able to offer similar transformational therapies to others through gene therapies we are developing, and other approaches.

Equally rewarding is watching young researchers I’ve mentored grow into independent leaders in their own right.

Science is a relay, not a sprint, and those moments remind me that progress is shared across generations.

What makes Australia a great place for medical research?

Australia has a remarkable culture of collaboration and innovation.

We have world-class researchers who are generous with their time and ideas, a health system that facilitates translational research, and patients who are willing to take part in cutting-edge clinical trials.

There’s also a wonderful sense of community – people genuinely want to see each other succeed.

At the same time, being part of a smaller scientific ecosystem encourages creativity and agility.

It’s the kind of environment where bold ideas can take shape and thrive.

In 10 years, what do you think will be the biggest change in ophthalmology thanks to research happening today?

I believe we’ll look back on this decade as the moment when ophthalmology moved decisively into the era of regeneration.

Treatments that go beyond slowing disease and towards restoring function will become a reality.

Advances in gene and cell therapy, neuroprotection, and bioengineering will converge to preserve and even recover sight in conditions like glaucoma and optic neuropathies.

Artificial intelligence will also redefine diagnosis and patient management, but the truly transformative change will come from our growing ability to repair the visual system itself.

If not ophthalmology, what do you think you would be doing?

I’ve always loved music and once imagined combining that passion with physics as an acoustic engineer.

It would have been a spectacularly impractical career choice, but there’s something about the intersection of art and science – whether it’s the harmony of sound or the clarity of vision – that has always appealed to me.